The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge and its Role in the Indian Mutiny of 1857

by Daniel R. LeClair

IAA Journal Issue 504, July/Aug. ’15

Of all the English colonial wars fought during the reign of Queen Victoria, none arrested the attention of the home population like the Indian Mutiny of 1857. Tales of atrocities, daring escapes, valour on the battlefield and the retributions that followed shocked and fascinated the British public. Thousands of books on the rebellion have been published, from the first year of the conflict until very recently. While the causes behind the rebellion are complex and open to interpretation, most historians agree that the “greased cartridge affair” triggered the uprising of sepoys in the service of the East India Company in May of 18571. Despite its significance, however, historians have consistently either reduced descriptions of the affair to a brief summary, or recorded its details incorrectly. In both cases, historians run multiple risks: misplaced culpability for the revolt, dismissal of Indian objections with simplistic explanations of religious superstition, or making errors that reduce the value of the work that the scholar has, most likely, spent years preparing.

When technology plays a role in historical studies, the details are important. By examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridge and the historiography of the “greased cartridge affair,” this article explores both the validity of Indian objections to this new type of ammunition and corrects some oft-repeated mistakes regarding the construction of the cartridge. In doing so, I hope to both to reinforce recent theories of the intentional use of the “greased cartridge affair” by Indians as a pretext for revolt, and to reduce whatever blame the English government bears for introducing the new Enfield cartridge into India in the first place.

The Greased Cartridge in Historical Writings

There has been considerable debate over the years regarding the significance of the events collectively referred to as the “greased cartridge affair.” On one extreme, Benjamin Disraeli dismissed the affair in a speech before Parliament with the claim that “the decline and fall of empires are not affairs of greased cartridges.”2 On the other extreme, Radical MP David Urquehart predicted “the French on the Ganges,” the loss of naval bases in the Mediterranean to the Turks, increased taxation, a cutoff of raw materials and collapse of British industry, all “because on the introduction of the Enfield rifle, the tearing of the cartridge was not substituted for the biting of it.”3

Many contemporary historians of the Indian Mutiny had very paternalistic interpretations of the “greased cartridge affair,” which reduced sepoy reaction to the new cartridge to near child-like misunderstandings. A section from John Kaye’s 1880 history serves as a good example, and reads very much like a fiery church sermon. Kaye opened with a discussion of the decision to replace that “relic of barbarism,” the older Brown Bess smooth-bore musket, with the rifled Enfield. He then went on to state that at first, “...the Sepoy rejoiced in the advantage which would thus be conferred upon him in battle, and lauded the Government for what he regarded as a sign both of the wisdom of his rulers and of their solicitude for his welfare.” “Unhappily,” Kaye continued, the new rifle “could not be loaded without the lubrication of the cartridge. And the voice of joy and praise was suddenly changed into a wild cry of grief and despair when it was bruited abroad that the cartridge, the end of which was to be bitten off by the Sepoy, was greased with the fat of the detested swine of the Mahomedan, or the venerated cow of the Hindoo.”4 Kaye also displayed the classic prejudicial view of the Indian native as in need of wise European guidance in his depiction of General Hearsey’s address to the troops at Barrackpore when trying to quash rumours regarding grease-impregnated paper. Kaye wrote that Hearsey “began to explain to [the native troops], and wisely too, as he would explain to children, that the glazed appearance of the paper was produced by the starch employed in its composition.”5

G. B. Malleson exhibited the same prejudice in his 1892 revision of Kaye’s work. Writing about the refusal of the 19th Native Infantry to use even old ammunition, he stated that the sepoys refused the cartridges for fear of losing their caste. “The reader may ask how that was possible,” he wrote, “considering that the cartridges were similar to those they had used for a century.” His answer “is that fanaticism never reasons.” “The Hindus are fanatics for caste,” Malleson continued. “They had been told that their religion was to be attempted by means of the cartridges, and their minds being... in an excited and suspicious condition, they accepted the tale without inquiry.”6

There is a good deal wrong with such statements. Overlooking the fact that both Hindu and Muslim soldiers made up Bengali sepoy regiments, Malleson’s interpretation pins blame for the Mutiny on the “fanatic” Hindu. At the same time, the implied gullibility of the Indian makes him innocent. The native soldier “had lost faith in the Government he served....[and] was ready to be practised upon by any schemer. His mind was in the perturbed condition which disposes a man to believe any assertion, however improbable in itself.”7 Such a statement makes the idea of intentional, planned resistance on the part of the sepoy simply vanish.

Indian nationalist Vinayak Savarkar, on the other hand, deliberately exaggerated the issue of “greased cartridges” in his 1909 work The Indian War of Independence of 1857. Savarkar wrote that “suspicions arose [among the sepoys] that the Feringhis had arranged a cunning plot to defile their religions by greasing the cartridges with cows’ blood and pigs’ fat.”8 A government official, or sirkar, told the men that the rumour was without foundation, but Savarkar challenged the truth of the matter, asking “who was it then that spoke the lie? Was it the Sirkar or the sepoys? If the cartridges were really greased with cows’ blood and pigs’ fat, was it the result of mere ignorance or of conscious purpose on the part of the Government?” Savarkar charged that “even the Commander-in-Chief knew the fact [in 1853] and, in spite of this, the very things prohibited by the two religions were used and even factories for their manufacture were opened right in India!”9

Savarkar, who used Kaye and Malleson for sources (among others), wrote a deliberately sensationalized and anti-British account which caused his book to be banned in England even before publication.10 Unfortunately, over the one hundred and fifty-plus years that separates the uprising at Meerut and today, many writers have either forgotten or misinterpreted the details of the cartridge itself, and the lengths the British Government went to allay religious fears regarding the grease used. Saul David, in his otherwise excellent article “Greased Cartridges and the Great Mutiny of 1857: A Pretext or the Final Straw?” wrote that the Bengal Army’s Ordnance Department “made the fatal, and unforgiveable, error of not specifying what type of tallow was to be used” in the local manufacture of Enfield cartridges, a charge he repeats in a 2009 work.11 In light of the actual construction of the cartridge, which will be discussed later, this statement is unduly harsh. The Ordnance Department did not specify the composition of the tallow not out of cultural insensitivity, but because it was immaterial. As will be shown, the greased end of the cartridge was opposite the portion a soldier needed to bite; there was little chance of any grease touching his lips at all during loading.

In addition, David’s opinion is coloured by misinterpretation of testimony given by Lieutenant M. E. Currie during the 18 March 1857 court martial of a sepoy of the 70th Native Infantry, repeated in one of the most recent examinations of the causes of the Indian Mutiny, Kim Wagner’s The Great Fear of 1857: Rumours, Conspiracies and the Making of the Indian Uprising. Both authors make the common error of confusing a bullet (the projectile being fired) with a cartridge (the container holding the bullet and powder), David writing that “the Enfield rifle’s grooved bore required the bottom two-thirds of its cartridge to be greased to facilitate loading.”12 Lieutenant Currie actually stated that “two-thirds of the bullet is dipped in grease.”13 Even that is technically incorrect, as the grease was applied to the outside of the cartridge, from its base up two-thirds the length of the bullet.

Other historians have made more grievous errors. Randolph G. S. Cooper, in his review of David Harding’s Small-arms of the East India Company 1600-1856, excoriated a “noted Western author, who shall remain nameless” for the “dental improbability” of sepoys biting the bullets from 1888 .303 Lee-Enfield rifles. “Yes, cartridges were bitten as part of the muzzle-loading procedure in those days, and yes there were ‘Enfield’ rifles in India during 1857,” Cooper wrote. “But the Lee-Enfield was a much later breech loading bolt-action repeater, as opposed to a single-shot muzzle-loader,” he pointed out, “and Lee-Enfield cartridges were not made of paper; rather they featured full-metal-jacket projectiles crimped into brass casings.”14

Another author, Alexander Llewellyn, described the greasing of cloth patches (used to wrap the bullets for earlier rifles) as the source of discontent, in his 1977 work The Siege of Dehli. “It was no wonder,” Llewellyn wrote, “that by April of the year of storms, many sepoys feared that a greasy patch of calico might be the talisman that would charm away their heritage;” a lovely bit of prose, but fundamentally wrong.15 Only the earlier Brunswick rifle required cloth patches, to allow the bullet to engage the rifling, and those patches were greased with non-animal fats. The Enfield rifle, as we will see, required no such loading procedure.

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones (no known relation to the above author) incorrectly described the construction of the Pattern 1853 cartridge, as well as the loading procedure, in her 2007 work The Great Uprising in India, 1857-58: Untold Stories, Indian and British. As will be shown, the tradition of biting cartridges extended back over a hundred years; Llewellyn-Jones, however, stated that “it was not the rifles that the sepoys objected to using, nor the cartridges supplied with them, but the screw of greased paper in which the cartridges were individually wrapped.” The bullets were not individually wrapped; instead, they formed an integral part of the Pattern 1853 cartridge. She compounded the mistake by claiming that “instead of tearing off the top of the paper pouch with the fingers, the old practice, the sepoys were now ordered to bite it off and spit it out...”16 This reverses the order of the changes in loading practice adopted for the new rifle; in addition, tearing would become part of the new loading procedure as a result of Indian concerns.

It is important, then, to examine the actual construction of the Pattern 1853 cartridge and the mechanics of musket loading – a task to which we now turn.

The Cartridges of the East India Company Army

The Honourable East India Company (HEIC, or simply, the Company) armed its native infantry sepoys with the same weapons used by the English Army. For a great deal of the eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century, most soldiers carried the large-caliber (.75-inch) smoothbore “Brown Bess” flintlock musket. As with most other military weapons of the age, ammunition consisted of a pre-assembled cartridge: a paper tube tied at the nose with the bullet placed inside, powder on top, and folded at the end, commonly called the tail. Smoothbore muskets fired spherical lead bullets that fit loosely in the barrel; the cartridge paper provided enough grip to prevent the bullet from rolling out when the musket pointed downward. The paper also prevented the escape of exploding gunpowder gases from around the bullet, a potentially dangerous situation that could damage the barrel and render it useless. Cartridges loaded with both bullet and powder were referred to as “balled” or “shotted;” those loaded with powder only, on the other hand, were referred to usually as “blanks,” but occasionally as “light” or “blunt” cartridges. Blanks were used for training, mock battles, saluting, and other noise-making purposes where a balled cartridge would prove hazardous to an army’s own troops. From 1811 onwards, blank cartridges were made of blue paper (as opposed to white), to provide better visual recognition and prevent accidents.17

Although the Brown Bess went through numerous changes, the loading drill, standardized in 1740, remained unchanged for nearly a century, dictated by the construction of the service flintlock musket. To prime, the soldier first held the musket horizontally, pulled open the priming pan cover, then “took a cartridge, tore open the powder end with his teeth, shook a little powder into the [priming] pan and shut it.” Shifting the weapon to the vertical position, he “poured the remainder of the charge into the muzzle and immediately pushed in the rest of the paper tube, still containing the ball at the top, and rammed it down the bore.18 When the Army transitioned from flintlocks to the Pattern 1842 percussion-primed musket, the ammunition did not change, as the weapons had the same sized bore, but the loading drill did. The soldier started with the musket held vertically, grasped the cartridge in the right hand, and bit the end off “so as to feel the Powder in his Mouth.”19 He then poured the powder down the barrel, placed the remainder of the cartridge in the muzzle, and rammed it home as before. At this point the soldier then placed a percussion cap on the nipple that served as both anvil and flash-tube to the main powder charge. The priming step, therefore, moved from before to after loading the weapon, but the step of biting the cartridge remained. This is in distinct opposition to Savarkar’s claim that orders issued for new loading drill required the sepoys to bite open the cartridge with their teeth, “instead of tearing it away with hands as formerly.”20

Figure 1 – 17: Components of the Pattern 1853 .577 Enfield cartridge, from an 1864 book of lithographs of products manufactured at the Royal Laboratory, Woolwich, England. [Below: enlargement for clarity] By the 1840’s, the days of the smoothbore musket were numbered. Accuracy was poor; even in the hands of well drilled troops, hit rates dropped significantly after 100 yards. At longer ranges, “few shots found their marks, and not only was ammunition wasted...the enemy were encouraged by the fire’s ineffectiveness, and one’s own men were disheartened and became ‘unsteady in the ranks’.”21 Accuracy could be improved by rifling the barrel, which imparted spin to the projectile and stabilized it in flight; rifling also required a much tighter fit between the bullet and the barrel wall. To accomplish this, shooters wrapped the round lead ball in a greased cloth patch; this engaged the rifling to get the spin desired, and also partially cleaned the rifle bore of residue from previous firings. Loading a rifle in such a manner required additional motions, however, as well as considerable effort to force the ball down the barrel; this not only slowed the soldier down, but the exertion of loading could affect the soldier’s aim. Units of riflemen were fielded by both the British and Company armies, but by and large they were specialized units. The average infantry regiment in all armies fought and trained with smoothbore muskets at the time of the mutiny.

A number of inventors in Europe devised alternative means of loading rifles, but Captain Claude-Etienne Minié of the French Army developed the most effective solution.22 Instead of the traditional round ball, Minié used a cylindrically-shaped bullet with a rounded nose and a hollow base lined with a thin iron cup. On firing, the exploding gunpowder would force the cup into the base of the bullet, flaring out the side walls and engaging the rifling. Since the bullet diameter was smaller than the rifle bore diameter, it required no lubrication for loading. Grease, however, served as an anti-fouling agent, preventing the build-up gunpowder residue in the rifling grooves and improving accuracy.23

Within a few short years, most major Western armies adopted rifled muskets using the Minié-style bullet, including England. After much experimentation, the Pattern 1853 Rifled Musket emerged as “arguably one of the finest muzzle loading rifles ever to be put into the hands of a soldier.”24 Standardized for adoption by both line and HEIC units, the rifle required a new form of ammunition. Although still paper, the Enfield cartridge was purpose-designed to keep the powder separate from the bullet (to avoid corrosion) and increase the new weapon’s potential for accuracy, while at the same time allow it to be loaded and fired at very near the speed of a smooth-bore. The construction of the cartridge made it an important component of the rifle “system” and bears closer investigation.

A single round of Pattern 1853 ammunition actually contained a surprising number of components, including three different pieces of paper: one for the powder, and two for the outside cylinder that held the bullet. Assembled by hand, the worker began with a slightly stiffer “cylinder paper” (Fig. 2), and rolled it around the “former” (Fig. 6). He then placed put the nose of the bullet - the smooth-sided “Pritchett” version of the Minié, Fig. 7 & 8 – into a recessed section of the former. Then, the worker layed the assembly atop the “outside forming paper” (Fig. 3) so that the walls of the bullet fell within three parallel cuts. Most likely a post-Crimea improvement, these cuts allowed the paper cartridge to be more easily broken off after loading, but also allowed the paper to separate cleanly from the bullet on firing. Otherwise, paper clinging to the bullet “produce[d] a peculiar whizzing sound” and decreased its accuracy. Once rolled, the remaining paper at the nose could then be choked and tied. Afterwards, a separately-rolled “powder bag” formed from the “inside forming paper” (Fig. 1) is pressed down into the completed cylinder to rest upon the nose of the bullet; a white band of paper (Fig. 4) is then pasted over the joint between the outer and inner cylinders. The powder charge would then be poured in and the tail of the cartridge twisted to close the entire assembly.25

Two major factors helped establish the final design of the Pattern 1853 cartridge: the requirement that the Minié bullet be seated in the barrel in the proper direction, and that the anti-fouling grease coat as much of the bore of the rifle as possible. The solution entailed not only the “reversed-loading” of the Pritchett bullet, described above, but also the last step in the Pattern 1853 ammunition construction: lubrication. Once charged with powder, the bullet section was dipped in melted grease, no more than about a third of the way up the cartridge tube, at the highest point of contact between the bullet and the rifle barrel wall. The “greased cartridge,” then, only had enough grease as required; any higher up would have been wasted. This style of cartridge construction was not unique to England; cartridges manufactured in France, Belgium, Switzerland and other countries which adopted the Minié bullet used the same construction.26

The “reversed” bullet design ensured that grease went all the way down to the powder charge, while at the same time making loading faster, but the change in cartridge construction required a change in loading procedure. The soldier still bit the powder-end of the cartridge off as before, and poured the powder down the barrel. He then flipped the cartridge end-over-end in order to press the bullet into the muzzle. Then, after breaking the remains of the paper tube off, he rammed the charge home. Although the change added an extra step, the improved accuracy of the Pattern 1853 weapon theoretically made up for any marginal decrease in load time. In contrast, the American style “non-reversed” cartridge required that the outer paper wrapper be peeled off the bullet before seating.27 This step could take slightly longer, and in the heat of battle the soldier might accidentally drop the bullet. The tactics of the time required the soldier to follow precisely the movements required load and fire in time with his fellow soldiers; stopping to pick up a dropped bullet would mean the difference between delivering an effective volley or throwing the timing of the entire company off.

Both the location and composition of the cartridge grease are of utmost importance to our story. Because of the great distances involved, regular shipments of small-arms ammunition from Britain to India were impractical; the HEIC therefore built its own system of arsenals to supply its regiments. England did ship experimental batches of factory-greased cartridges to India for handling and climate tests in 1853 – but not for firing trials.28 The ammunition either stayed in storage at the arsenals, or packets were placed in cartridge pouches carried by Indian guards to see how the cartridges stood up to daily handling. In 1855, the entire batch returned to England. Dum-Dum Arsenal received a much larger shipment from England in 1856, to meet expected training and practice requirements. Those cartridges were shipped dry, to prevent the grease from being absorbed by the paper while in transit; Indian arsenals were responsible for greasing the cartridges in-country.29

J. A. B. Palmer claimed, in his oft-cited 1966 work The Mutiny Outbreak at Meerut in 1857, that “the grease made at Enfield was composed of tallow from beef and pork fat.”30 This is incorrect on two counts. First, Enfield made only the rifles; government small arms ammunition manufacture was the responsibility of the Royal Laboratory at Woolwich. Second, the test batch consisted of cartridges greased with four different compositions, the actual make-up of which is lost to history.31 A memorandum from the Inspector-General of Stores (No. 46, dated 7 February 1857), however, indicated that the Laboratory used a grease mixture of five parts tallow, five parts stearine (a more refined form of tallow), and one part wax, presumably to strengthen the compound. “As these ingredients are purchased in large quantities and delivered to Woolwich,” the memo states, the Laboratory could not say exactly what animal the tallow derived from, only that “hogs’ lard does not, in any way, enter into the composition.”32 Even if pig fat had been a part of the 1853 test batch, the Laboratory rejected it for future use.

Figure 18: A very scarce packet of Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridges from the Crimean War. Kindly reproduced with the permission of the Royal Armouries, Leeds. (Ref: XII.10598)

Figure 19: a Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridge most likely manufactured at the Royal Laboratory circa the Indian Mutiny. The tail of the powder bag shows a seamless, mottled brown paper, indicative of as being made on-site from pulp rather than a cut sheet. Inspired by similar machinery then being used to manufacture tea-bags, RL tried to make both the inner and outer tubes from pulp with mixed success; Arthur B. Hawes, in his 1859 booklet on Rifle Ammunition; Being Notes on the Manufacturers Connected Therewith, as Conducted in the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, wrote that “as yet... no very satisfactory result has been obtained.”

Source: author’s collection.

With general issue pending for 1857, training with the new rifles commenced at regional Indian arsenals at some point in 1856. The arsenals had facilities for the storage and repair of weaponry, as well as for the manufacture and storage of small-arms and artillery ammunition. Each also had its own training depot, responsible for small-arms instruction. Select parties of seven men each from the regiments destined to get the new rifles went to these training depots for initial instruction on “the mechanism and care of the weapon covered by the Manual Exercise.” No firing drills were scheduled until 1857, and the men would not have handled Enfield cartridges until then, if at all.33

The “Greased Cartridge Affair”

The rumour regarding cartridges greased with religiously objectionable material first appeared at the Dum-Dum training depot. On 22 January 1857, Lieutenant Wright (70th Native Infantry) reported to his commander a “very unpleasant feeling among the native soldiers… regarding the grease used in preparing the cartridges, some evil-disposed person having spread a report that it consisted of a mixture of the fat of pigs and cows.” Lieutenant Wright continued that a worker at the arsenal had been rebuked by a sepoy of the 2nd Grenadiers after the former asked for a drink from the latter’s canteen. Refused because of a difference in caste, the worker retorted the soldier “‘will soon lose your caste, as ere long you will have to bite cartridges covered with the fat of pigs and cows,’ or words to that effect.”34 The last phrase emphasizes that this report consisted of rumour, not an exact quote. Major-General Hearsey, commander of the Barrackpore cantonment forwarded a slightly modified version to the Secretary of the Government of India on 11 February, which changed what the laborer said to “the Sahib-logue will make you bite cartridges soaked in cow and pork-fat.”35 In either case, it implies that grease covered the whole of the cartridge, which, as we have seen, is incorrect.

Shortly after the rumour surfaced, the Governor-General’s office asked the Inspector-General of Ordnance (IGO) about the grease composition used at the Dum-Dum arsenal, specifically “whether mutton fat...is used, and if there are any means adopted for ensuring the fat of sheep and goats only being used.” The IGO replied that the grease, a mixture of tallow (of unspecified nature) and beeswax “in accordance with the instructions of the Court of Directors,” had been supplied by a contractor. Unfortunately, the details of the instructions and the nature of the tallow that contractor actually supplied are unknown. “No extraordinary precaution appears to have been taken to ensure the absence of any objectionable fat,” wrote the IGO, nor were any cartridges made without grease; the latter idea “did not occur to him.”36

Regardless, the IG moved quickly to prevent any greased cartridges from getting into the hands of native troops. Arsenals suspended the complete preparation of Enfield cartridges, and all magazines of the Upper Provinces in the Bengal Presidency were ordered to only issue ungreased cartridges.37 Soldiers were also authorized to purchase their own ingredients (usually ghi, a form of clarified butter, and beeswax) from the local market, in order to grease the cartridges themselves.38

By the outbreak of the Mutiny, only 12,000 rifles had been received by the Bengal Presidency, with most going into storage and a small number to the training depots. Only one British unit (1st Battalion, 60th Queens Royal Rifles) had been issued the weapons.39 With the exception of the men rotating through the training depots, few sepoys actually saw an Enfield rifle cartridge, greased or otherwise. Possibly because of this, by February, the nature of sepoy complaints changed, from concern about the grease on the new cartridge, to concern regarding grease in the paper of any cartridge, old or new.

The paper used for smooth-bore cartridges had specific requirements, aside from the colour coding required for blanks. It had to be of a consistent thickness (to prevent the ball wrapped inside from getting stuck in a barrel on loading), resistant to damage from humidity, durable enough to be carried in the standard ammunition pouch, yet still soft enough to allow the nose to be tied and for the tail to tear off easily.40 Until 1842 the Company imported cartridge paper from England, although locally-made paper could be used for blank ammunition. Beginning in 1842, however, a mill at Serampore began manufacturing paper of a quality near enough for balled cartridges. Additional quality improvements were made, as well as price reduction, and in 1846 the paper was approved for use in Bengali arsenals, with Madras following a year later.41

The source of paper used for Enfield cartridges made in India is unknown, but a supply of English paper may have been included along with new moulds required for the Pritchett bullet. Regardless, in early February, General Hearsey reported that both native officers and sepoys had developed “a most unreasonable and unfounded suspicion…that grease or fat is used in the composition of this cartridge paper; and this foolish idea is now so rooted in them, that it would, I am of opinion, be both idle and unwise even to attempt its removal.”42 Hearsey recommended that the same paper used previously to make up the “common musket cartridge” be used to make up the rifle cartridge. By then, however, the rumour regarding the cartridge paper had caught hold. In a later court of inquiry, witnesses claimed that the “glazed, shiny or waxed appearance, a stiffness, a difference from the old paper, and...a report that it was impregnated with grease” made them suspicious of the cartridges.43 Others later testified that paper from ungreased cartridges “made a fizzing noise when burned and smelt as if there was grease in it.”44 Clare Anderson claimed in her 2007 work on Indian prisons at the time of the Mutiny that the cartridges used “gelatine-stiffened” paper, but this has not been corroborated by primary sources; the “fizzing noise” would easily have been caused by residue from the powder charge.45 Regardless, no amount of reassurance from their European officers seemed to convince the sepoys that the paper did not contain grease.

By the end of February, suspicion of the paper had passed to old Pattern 1842 cartridge as well. Sepoys of the 19th Native Infantry at Baharampur refused to take percussion caps for their weapons when served out the afternoon of 26 February for a scheduled firing drill with blank ammunition. A petition from the men of the regiment later explained that rumours regarding new cartridges “on the paper of which bullock’s or pig’s fat was spread” had been circulating for over two months. Fresh stores of ammunition had been recently sent up from Calcutta; on the afternoon of the 26th, when inspecting the two kinds of cartridges to be fired the next day, “one sort appeared to be different from that formerly served out.” The petition went on to state that the sepoys “doubted whether these might not be the cartridges which had arrived from Calcutta, as we had made none ourselves, and were convinced they were greased.46

That evening, regimental commander Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell explained to the native officers that the blank ammunition had been made up the year before by a different Indian regiment, and that “they had better tell the men of their companies that those who refuse to obey the orders of their officers are liable to the severest punishment.”47 The sepoys, however, took matters into their own hands, seizing weapons and ammunition and loading their muskets, regardless of any notion of contaminated paper. The sepoy petition reports of “being surrounded by Europeans” and that the arrival of guns and cavalry triggered the seizure of arms. Mitchell, however, stated that he did not order out support from nearby cavalry and artillery units until after disturbances among the sepoy lines had been reported.48

Regardless, this incident of near-mutiny over fear of biting tainted cartridges would not be the last. On the afternoon of 29 March, Mangal Pande, a sepoy in the 34th Native Infantry at Meerut, attempted to raise mutiny in his own regiment, shouting for his fellow soldiers to “come to his aid for the sake of religion, as they would be forced to bite the cartridges.”49 Pande wounded two English officers, and then attempted to kill himself. He survived the attempt, only to be court-martialed and hanged on 6 April.

That same month, the Indian government made a change to the official loading drill in another attempt to remove fears of religious contamination by grease. Instead of biting open the cartridge, soldiers would tear the tail off with their left hand (while holding the cartridge in their right as before). It is important to note here that Indian suspicions regarding the cartridges specifically centred on the biting, not the handling, of potentially tainted ammunition. Firing practice with the new rifle, which had been suspended, was ordered to get under way. Shooting resumed at Dum-Dum and Sialkot without incident, but other arsenals saw a wave of arson attacks, including at Meerut, where the mutiny finally broke out. Again, the disturbance began over blank cartridges to be issued for a mock skirmish. Scheduled to be done with old cartridges, two Muslim corporals supposedly spread the rumour that new cartridges greased with pork and beef fat would be issued, and a group of men swore not to use the cartridges until the entire regiment agreed to do so.50 Although later testimony showed that, as with the incident at Baharampur, the blank ammunition had been made up the year before and with the same paper as usual, the rumour quickly spread.51 Captain Craigie, commander of the 4th Troop, 3rd Light Cavalry, reported that although “we have none of the objectionable cartridges…the men say that if they fire any kind of cartridge at present they lay themselves open to the imputation from their comrades and from other regiments of having fired the objectionable ones.52

When it came time to issue ammunition for the skirmish on 24 April, eighty-five of ninety men refused the cartridges; a subsequent court-martial sentenced the men to ten years’ hard labour. On 9 May, 1857, the defendants were paraded before their fellow soldiers, shackled, and led off to jail. The event took two hours, not counting the two-mile march to the jail, during which the condemned cried out for rescue, taunted their comrades, and hurled abuse at their officers.53 The next evening the sepoys of the 20th Native Infantry at Meerut revolted, joined later by the 3rd Light Cavalry and many civilians from the local bazaar. The cavalry broke the imprisoned men out of jail, and rioting soldiers turned their muskets against their European officers. The Indian Mutiny had begun.

Conclusion

“All historians have the responsibility of separating truth from error,” wrote Christopher Herbert in his 2008 work on the Indian Mutiny, and this is especially true in works of socio-technological history.54 In the case of the Indian Mutiny, some questions remain unresolved, particularly the issue of conspiracy to promote the “greased cartridge” as a reason for mutiny. Any suspected ringleaders were either hanged, shot out of hand, or found themselves strapped to the muzzles of cannon – and left no written records to boot. Contemporary English chroniclers as well as Savarkar supported the theory of a centrally-guided conspiracy, to which Saul David gives some credence, as the sepoys of many regiments regarded the greased cartridge reports with ambivalence, at least until the mutiny actually broke out. “The cartridge question,” David wrote, “was only of interest to those who wished to foment mutiny... [the] perfect vehicle for conspirators to turn the rank and file of sepoys against British rule.”55 Knowing the amount and intended purpose of grease on the cartridge actually reinforces his thesis.

Kim Wagner, on the other hand, discounts such theories. Wagner suggests that, for Indian sepoys, the Enfield cartridge represented “a direct attack on their culture and society.” “Whether the objection to the cartridges should be attributed to an actual belief that the grease was polluting,” he continues later, “or whether group pressure and the fear of being ostracised by friends and kin weighed more heavily, the cartridge issue constituted a unique symbol around which sepoy disaffection consolidated.”56

Conspiracy or no, it is clear from an examination of the Pattern 1853 cartridge that Indian sepoys made a conscious effort to use the “greased cartridge” as a vehicle for action against the Company. No amount of explanation or modification seemed to placate those interested in making a stand on the issue. In fact, David quotes a lieutenant of the 3rd Light Cavalry as saying that the “Bengal native army [made] the cartridge question a test as to which was stronger – the native soldier or the Government.”57 By considering the amount and placement of grease on the Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridge, the reasons for greasing it, the fact that few Indians ever actually handled a “greased cartridge” and that mutinying Indian sepoys had no qualms regarding the biting of supposedly “tainted” cartridges, the lieutenant’s statement rings even truer.

Ultimately, Government proved stronger; only a certain portion of the vast HEIC holdings joined the rebellion, and the superior accuracy of the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle proved telling on the field of battle. Ironically, the use of tallow for coating the bullet portion of the Enfield cartridge proved to be a bad choice; the bullets in cartridges so treated oxidized rapidly in storage, to the point where they no longer fit down the barrel. In 1857, the Royal Laboratory switched to pure beeswax as the material to be used as the anti-fouling agent of the Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridge.

Indian conspirators and English politicians weren’t the only ones to look for advantage from the “greased cartridge affair.” Twenty-two patents related for muzzle-loading cartridges were filed between 10 May 1857 and the end of 1863 (fifteen alone in 1858-59, as opposed to two in 1855 and none in 1856). Two (one by “G. Hall” and the other by “T. Hall,” no known relation) specifically mention that their design eliminated “the necessity for biting off the ends.”58 The others make clear the bullet and powder could be loaded either by ramming alone, or tearing the cartridge open. Two covered different types of lubricant for cartridges. J. Scoffern’s patent (No. 864, 6 April 1859) specified cartridges “dipped in a melted mixture, consisting of equal weights of paraffin and napthalene [sic], or of india-rubber mixed with four times its weight of paraffin and half its weight of napthalene.”59 That of J. J. Mundy (No. 1346, 31 May 1859) covered “cartridges and wads” treated with dry lubricant: “talc, steatite, graphite, iron carbide, micaceous iron ore, ‘Devonshire shining lead ore,’ or the like.”60 With the exception of the Whitworth tubed cartridge (designed for use in a specific rifle, although the cartridge could have been adapted to the Enfield) none of the patents saw any large-scale production.61 The British army stuck with its simple change to the firing drill and use of pure beeswax as lubricant for the Enfield cartridge to avoid any further religious objections from using the Pattern 1853 cartridge in the future.

The Indian Mutiny is one of those instances where a small military store had an impact far out of proportion to the intention of its inventor. Designed as part of an improved rifle “system” giving the infantryman a much more accurate weapon, the “greased cartridge” instead provided the spark for a conflagration that cost many thousands of lives, as well as imperilling English possession of a territory considered to be the “jewel of the Empire.” As such, the Pattern 1853 Enfield cartridge should be understood for what it was and how it was constructed, in addition to the role it played in the Mutiny.

Figure 20: A standard cartridge for the Pattern 1842 musket.

Source: Pete deCoux collection.

Figure 21: An interesting specimen which lacks the paper strip normally uniting the inner and outer cylinders. The mottled colour of the pulp powder bag is very clear.

Source: Will Adye-White collection.

Figure 22: Another interesting variation stamped “ELEY BROs LONDON. ” It too lacks the white cylindrical strip.

Source: Will Adye-White collection.

Figures 23 & 24: A very scarce example of a civilian load with an identification band indicating manufacture by W. Pursall Ltd. Most civilian ammunition, once out of its ten-round paper wrapper, lacked any way to determine its origin.

Source: Will Adye-White collection.

-------------

1. The term “sepoy” comes from the Persian word sipahi, meaning “soldier.” Native Indian soldiers comprised the bulk of East India Company troops serving in India, although there were several regiments of white English soldiers. While sepoy regiments had Indian non-commissioned officers, all commissioned officers were white Europeans.

2 Motion for Papers, 27 July 1857 (http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/comm ... 727_HOC_16), 147:475.

3 David Urquhart, “The Rebellion in India: The Wondrous Tale of the Greased Cartridges.” In Pamphlets by Mr. Urquhart, Vol. II (London: Bryce, 1857), 10.

4 John W. Kaye, A History of the Sepoy War in India, 1857-1858 (London: W.H. Allen, 1880), 488-489.

5 Kaye, 534.

6 G. B. Malleson, The Indian Mutiny of 1857 (London: Seeley and Co., 1892), 38.

7 Malleson, 16-17.

8 “Feringhi” is a Persian word meaning “foreigner,” and a term often used by Indians to refer to the English.

9 Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar. The Indian War of Independence of 1857 (London: Unknown publisher, 1909), 53.

10 Kim A. Wagner, The Great Fear of 1857: Rumours, Conspiracies and the Making of the Indian Uprising (Witney: Peter Lang, 2010), 14.

11 Saul David, “Greased Cartridges and the Great Mutiny of 1857: A Pretext or the Final Straw?” War and Society in Colonial India, 1807-1945 (New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 2006), 85.

12 David 2006, 85. He also made this mistake in his much larger book, The Indian Mutiny:1857 (London; Viking, 2002).

13 Appendix to Papers Relative to the Mutinies in the East Indies. (Inclosures in Nos. 7 to 19.) House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, 1857 Session 2, [2265],, 222. The italics, in both quotes, are mine.

14 Randolf G. S. Cooper, “Reviewed Work: Smallarms of the East India Company 1600-1856 by D. F. Harding.” Modern Asian Studies 36, no. 3 (2002), 760. The “nameless” author is most likely K. Theodore Hoppen, who made the error on page 188 of his book The Mid-Victorian Generation, 1846-1886, a volume of the New Oxford History of England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998).

15 Alexander Llewellyn, The Siege of Delhi (London: MacDonald and Jane’s, 1977), 15.

16 Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, The Great Uprising in India, 1857-58 : Untold Stories, Indian and British (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2007), 9.

17 David. F. Harding, Smallarms of the East India Company, 1600-1856 Vol. III: Ammunition and Performance (London: Foresight Books, 1997) 130.

18 Harding, 113.

19 Harding, 257.

20 Savarkar, 52.

21 Harding, 274.

22 George A. Hoyem, The History and Development of Small Arms Ammunition Vol. One: Martial Long Arms, Flintlock through Rimfire (Tacoma, WA.: Armory Publications, 1981), 31.

23 Arthur B. Hawes, Rifle Ammunition; Being Notes on the Manufactures Connected Therewith, as Conducted in the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich (London: W.O. Mitchell, 1859), 2.

24 Peter. Smithurst, “The Pattern 1853 Rifled Musket -- Genesis”. Arms & Armour 4, no. 2 (2007), 140.

25 Arthur B. Hawes, Rifle Ammunition; Being Notes on the Manufactures Connected Therewith, as Conducted in the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich (London: W.O. Mitchell, 1859; repr. Thomas Publications, Gettysburg PA, 2004) 35-41.

26 The author has examined specimens from various countries in the James Tillinghast collection; see also Hoyem, 36-40.

27 United States War Dept., “U.S. Infantry Tactics: For the Instruction, Exercise, and Manoeuvres of the United States Infantry, Including Infantry of the Line, Light Infantry, and Riflemen.” (http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/te ... 1.0001.001), 32.

28 Kaye (pg. 516) puts the year at 1853. G. Dodd (The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions to Persia, China, and Japan, 1856-7-8 (London, W. and R. Chambers, 1859, pg. 38) puts the year as 1854; that may have been when the shipment arrived in India.

29 Palmer, 11.

30 J. A. B. Palmer, The Mutiny Outbreak at Meerut in 1857 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1966), 11.

31 Dodd, 38. Dodd lists the compositions as “common grease, ...laboratory grease, ...Belgian grease, and...Hoffman’s grease, in each case with an admixture of creosote and tobacco.”

32 Papers relative to the Mutinies in the East Indies, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, 1857 Session 2 [2252] XXX.I.

32 Papers relative to the Mutinies in the East Indies, House of Commons Parliamentary Papers, 1857 Session 2 [2252] XXX.I.

33 Palmer, 14; also Saul David, The Bengal Army and the Outbreak of the Indian Mutiny (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 2009), 207. Palmer reports that five men from each regiment were sent; David reports seven (one European and one native officer plus five native non-commissioned officers).

34 Noah Alfred Chick, Annals of the Indian Rebellion, 1857-58 (Calcutta: Sanders, Cones and Co., 1859), 30. “Classie” is khalasi, a low-caste laborer; a lotah is a brass water pot, or canteen.

35 Chick, 30.

36 Henry Mead, The Sepoy Revolt; Its Causes and Its Consequences (London: J. Murray, 1857), 51-52

37 Appendix to Papers, 223.

38 Hearsey’s letter to the Deputy Adjutant-General of the Army, dated 28 January 1857, noted that “the letter permitting the ghee, or other material, to be used...only arrived this morning.” See Chick, 27.

39 David 2009, 86.

40 Harding, 126.

41 Harding, 137.

42 Mead, 53.

43 Palmer, 22.

44 David 2009, 88.

45 Clare Anderson, The Indian Uprising of 1857- : Prisons, Prisoners, and Rebellion (London; New York: Anthem Press, 2007), 3. Regarding powder residue clinging to paper, the author has considerable first-hand experience with the construction of cartridges for muzzle-loading weaponry.

46 Appendix to Papers, 265. Most Indian regiments made their own stocks of blank cartridges.

47 Appendix to Papers, 261.

48 Appendix to Papers, 261.

49 Palmer, 30.

50 Palmer, 60. Palmer mentions that evidence against the Muslims (who happened to be the first two men to later refuse the ammunition) was given by three Hindu soldiers, and therefore is not entirely without prejudice.

51 David 2009, 100

52 Palmer, 60.

53 Palmer, pg. 68.

54 Christopher Herbert, War of No Pity: The Indian Mutiny and Victorian Trauma (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2008), 137.

55 David 2006, 98-99, 103-104.

56 Wagner, 24, 219.

57 David 2006, 103.

58 Patents for Inventions: Abridgements of Specifications, Class 9, Ammunition, Torpedoes, Explosives, and Pyrotechnics, 1855-1866 (Love & Malcomson, London, England, 1905: Museum Restoration Service, Bloomfield, Canada, 1981) pg. 26.

59 Patents, Class Nine, pg. 34.

60 Patents, Class Nine, pg. 35.

61 Hoyem, pp. 44-45.[/i]

-------------

-------------

Bibliography

Anderson, Clare. The Indian Uprising of 1857-8: Prisons, Prisoners, and Rebellion Anthem South Asian Studies. London; New York: Anthem Press, 2007.

Chick, Noah Alfred. Annals of the Indian Rebellion, 1857-58. Calcutta: Sanders, Cones and Co., 1859.

Cooper, Randolf G. S. “Reviewed Work: Smallarms of the East India Company 1600-1856 by D. F. Harding.” Modern Asian Studies 36, no. 3 (2002): 758-764.

David, Saul. The Indian Mutiny: 1857. London: Viking, 2002.

Saul David, “Greased Cartridges and the Great Mutiny of

1857: A Pretext or the Final Straw?” War and Society in

Colonial India, 1807-1945. New Delhi, India: Oxford

University Press, 2006.

David, Saul. The Bengal Army and the Outbreak of the Indian

Mutiny. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors,

2009.

Dodd, G. The History of the Indian Revolt and of the Expeditions

to Persia, China, and Japan, 1856-7-8. London,

W. and R. Chambers, 1859

Fitchett, W. H. The Tale of the Great Mutiny. New York:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901.

Fox, Lane. “On the Improvement of the Rifle, as a Weapon for

General Use.” Journal of the United Service Institution.

Vol. II (1859): 453-493.

Greener, William W. The Gun and Its Development. Guilford,

Conn.: The Lyons Press, 2002.

Harding, David. F. Smallarms of the East India Company,

1600-1856 Vol. III: Ammunition and Performance. London:

Foresight Books, 1997

Hawes, Arthur B. Rifle Ammunition; Being Notes on the

Manufactures Connected Therewith, as Conducted in the

Royal Arsenal, Woolwich. London: W.O. Mitchell, 1859:

Thomas Publications, Gettysburg PA, 2004

Heathcote, T. A. Mutiny and Insurgency in India, 1857-1858:

The British Army in a Bloody Civil War. Barnsley: Pen

& Sword Military, 2007.

Herbert, Christopher. War of No Pity: The Indian Mutiny and

Victorian Trauma. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press, 2008

Hogg, Oliver Frederick Gillilan. The Royal Arsenal: Its Background,

Origin, and Subsequent History. London; New

York: Oxford University Press, 1963.

Holmes, T. Rice. A History of the Indian Mutiny and of the

Disturbances Which Accompanied It among the Civil

Populations. London: W.H. Allen, 1888.

Hoyem, George A. The History and Development of Small

Arms Ammunition, Vol. One: Martial Long Arms, Flintlock

through Rimfire. Tacoma, WA: Armory Publications,

1981.

Judd, Denis. The Lion and the Tiger: The Rise and Fall of

the British Raj, 1600-1947. Oxford; New York: Oxford

University Press, 2004.

Kaye, John William. A History of the Sepoy War in India,

1857-1858. London: W.H. Allen, 1880.

Leasor, James. The Red Fort; the Story of the Indian Mutiny

of 1857. New York: Reynal, 1957.

Llewellyn, Alexander. The Siege of Delhi. London: MacDonald

and Jane’s, 1977.

Llewellyn-Jones, Rosie. The Great Uprising in India, 1857-

58: Untold Stories, Indian and British. Woodbridge:

Boydell Press, 2007.

Logan, Herschel C. Cartridges: A Pictorial Digest of Small

Arms Ammunition. Huntington, WV: Standard Publications

Inc., 1948.

Majumdar, R. C. The Sepoy Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857.

Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1963.

Malleson, G. B. The Indian Mutiny of 1857. London: Seeley

and Co., 1892.

McCarthy, Justin. “Lady Judith: A Tale of Two Continents

(Chapter XXIX).” The Galaxy: An Illustrated Magazine

of Entertaining Reading Vol. XII, September 1871 (1871).

Mead, Henry. The Sepoy Revolt; Its Causes and Its Consequences.

London: J. Murray, 1857.

Palmer, J. A. B. The Mutiny Outbreak at Meerut in 1857.

Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

Roy, Kaushik, ed. War and Society in Colonial India, 1807-

1945. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar. The Indian War of Independence

of 1857. London: Unknown publisher, 1909.

Sen, Surendra Nath, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad. Eighteen

Fifty-Seven. New Delhi: The Publications Division,

Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of

India, 1977.

Smithurst, Peter. “The Pattern 1853 Rifled Musket -- Genesis.”

Arms & Armour 4, No. 2 (2007): 123-140.

“Trial of Muhammad Bahadur Sha, Titular King of Delhi,

and of Mogul Beg, and Hajee, All of Delhi, for Rebellion

against the British Government, and Murder of Europeans

During 1857.” Selections from the Records of the Government

of the Punjab and its Dependencies Vol. VII (1870).

Urquhart, David. “The Rebellion in India: The Wondrous Tale

of the Greased Cartridges.” In Pamphlets by Mr. Urquhart,

II. London: Bryce, 1857.

Wagner, Kim A. The Great Fear of 1857: Rumours, Conspiracies

and the Making of the Indian Uprising. Witney:

Peter Lang, 2010.

Appendix to Papers Relative to the Mutinies in the East

Indies. (Inclosures in Nos. 7 to 19.) House of Commons

Parliamentary Papers, 1857 Session 2, [2265].

Motion for Papers, 27 July 1857 (http://hansard.millbanksystems.

com/commons/1857/jul/27/motion-for-papers#

S3V0147P0_18570727_HOC_16),

Patents for Inventions: Abridgements of Specifications, Class

9, Ammunition, Torpedoes, Explosives, and Pyrotechnics,

1855-1866. Love & Malcomson, London, England, 1905:

Museum Restoration Service, Bloomfield, Canada, 1981.

United States War Dept., “U.S. Infantry Tactics: For the Instruction,

Exercise, and Manoeuvres of the United States

Infantry, Including Infantry of the Line, Light Infantry, and

Riflemen.” http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx-

?c=moa;idno=AJS4261.0001.001.

Historical background, Brown Bess musket: http://www.

militaryheritage.com/musket6.htm

For comparative examples of the loading and firing of flintlock

vs. percussion weapons, see the following videos:

• The Brown Bess Musket:

related

• An American Civil-War era Springfield rifle, very similar

to the British Enfield:

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Pete and Gaye deCoux for providing access to cartridges in the late Jim Tillinghast collection; and Will Adye-White.

The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge

- mundaire

- We post a lot

- Posts: 5415

- Joined: Mon May 22, 2006 5:53 pm

- Location: New Delhi, India

- Contact:

The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge

You do not have the required permissions to view the files attached to this post.

Like & share IndiansForGuns Facebook Page

Follow IndiansForGuns on Twitter

FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHTS - JOIN NAGRI NOW!

www.gunowners.in

"Political tags - such as royalist, communist, democrat, populist, fascist, liberal, conservative, and so forth - are never basic criteria. The human race divides politically into those who want people to be controlled and those who have no such desire." -- Robert Heinlein

Follow IndiansForGuns on Twitter

FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHTS - JOIN NAGRI NOW!

www.gunowners.in

"Political tags - such as royalist, communist, democrat, populist, fascist, liberal, conservative, and so forth - are never basic criteria. The human race divides politically into those who want people to be controlled and those who have no such desire." -- Robert Heinlein

-

KK20

- Fresh on the boat

- Posts: 4

- Joined: Thu Oct 25, 2018 7:24 pm

Re: The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge

An excellent read. Thank you for posting.

- xl_target

- Old Timer

- Posts: 3488

- Joined: Wed Jul 29, 2009 7:47 am

- Location: USA

Re: The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge

Don't know how I missed this article.

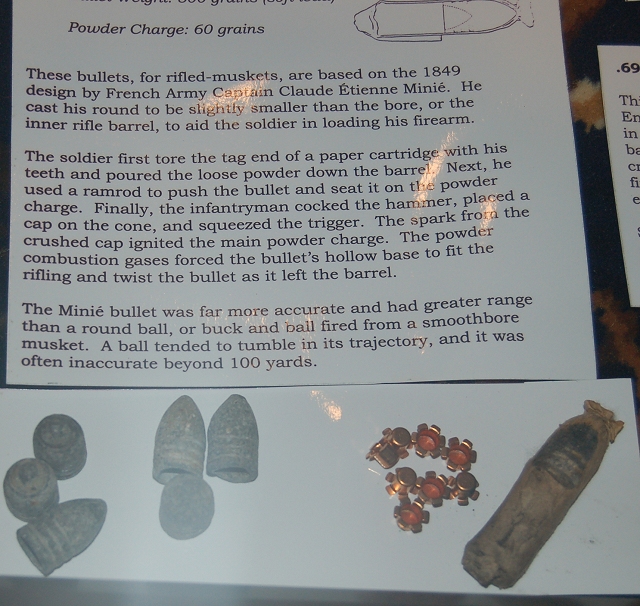

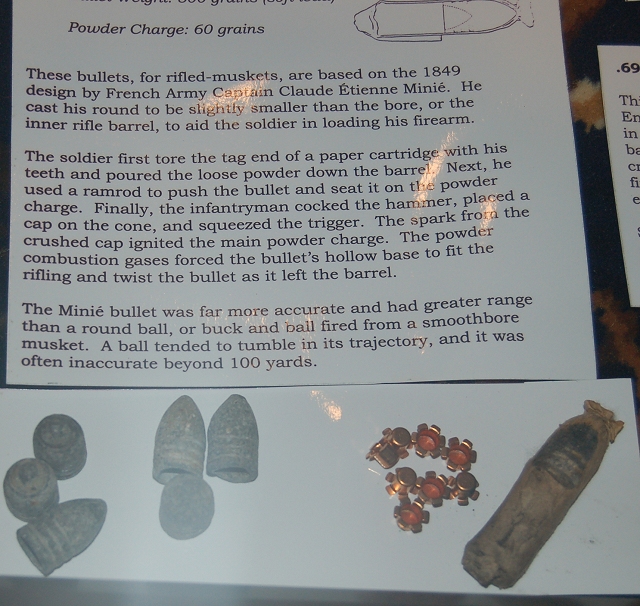

Below is the version of the paper cartridge used during the American Civil War (1861-1865)

Interesting similarities.

Below is the version of the paper cartridge used during the American Civil War (1861-1865)

Interesting similarities.

“Never give in, never give in, never; never; never; never – in nothing, great or small, large or petty – never give in except to convictions of honor and good sense” — Winston Churchill, Oct 29, 1941

-

panzernain

- On the way to nirvana

- Posts: 56

- Joined: Mon Mar 13, 2017 2:08 pm

Re: The “Greased Cartridge Affair:” Re-Examining the Pattern 1853 Enfield Cartridge

Such an amazing read. The most comprehensive yet on the greased cartridge affair.