My Mother always taught me that "a word to the wise is sufficient."

I want to describe some revolver lock mechaisms for you in connection with the issues raised by this thread.

A handgun must be ready to shoot if it is to function as a self-defense tool. The problem with this started back when guns were first invented that could be carried, but let me jump to the era of cartridge guns. I will use the famous old Colt "Six Shooter," or Single Action Army as an example.

This is a drawing of the lockwork parts of a Colt Single Action Army. Note the notches in the base of the hammer, into which, the sear part of the trigger engages to cock the hammer.

You see the firing pin on the hammer, which penetrates a small hole in the frame to strike the primer of a cartridge.

The problem with the Single Action Army is that, if there is a cartridge in the chamber underneath the firing pin when the hammer is down, or uncocked, a blow to the hammer can set off the cartridge.

If the hammer is carried in the half-cock notch (which is normally used for loading the cylinder), a sharp blow to the hammer, such as may happen when the gun is dropped, can break off the half cock notch and allow the firing pin to set off cartridge. This can also happen if the gun is carried on full cock.

Also, it can happen that the hammer can be inadvertently pulled back by, say, passing branches of a bush and under some conditions, the hammer may fall before the sear in the trigger can engage a notch, causing the gun to fire accidentally.

The old Colt Single Action was therefore a very unsafe gun to carry, ready to fire. Commonly they are carried with the hammer down and resting on an empty chamber, so that when the gun is to be brought into action, it must be cocked before firing. This practice means that the gun can only be carried with five cartridges loaded.

When double action revolvers began to be offered, the gun no longer needed to be cocked with the thumb to fire it. It could be carried with the hammer down over an empty chamber, brought to action, and fired, by pulling the trigger alone. This was safe, but it still meant that one chamber in the cylinder was empty, reducing the number of cartridges available to be fired.

One method of addressing the empty chamber was the "rebound lever."

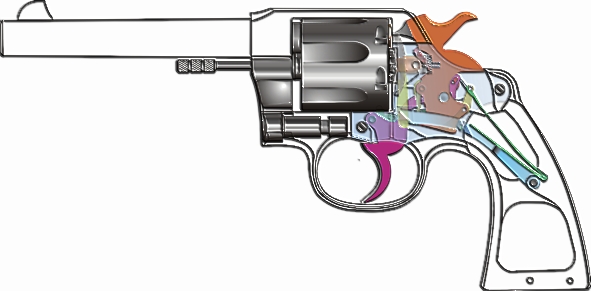

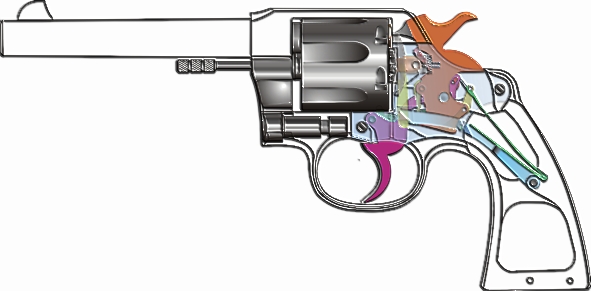

Please disregard the exact type of gun in this picture. I want you to notice the rebound lever, which is in blue and pivots half way down the grip. As it gets near the hammer, only part of its thickness passes on the left side of the hammer to rest on the point where the hand (the part that rotates the cylinder) pivots on the trigger. Thus, when the trigger is pulled or when the hammer is cocked in the full cock notch, the rebound lever rises. When the trigger is released, the rebound lever drops.

There is a part of the rebound lever that is located behind the hammer. The idea is that, when the hammer drops and fires a cartridge because the trigger is pulled, the rebound lever will go down as the trigger is released. It cannot "fall" all the way down, however, because the notched part behind the hammer rests on a surface on the bottom of the hammer. At this point, the rebound lever is pushed all the way down by a spring, and the notched surface on the rebound lever pushes the hammer back so that the firing pin is withdrawn.

This is the state the hammer will normally be in when the trigger is not pulled and when the hammer is not cocked. The gun can be loaded with all six cartridges (or however many the cylinder holds) and the firing pin will not rest on a loaded cartridge.

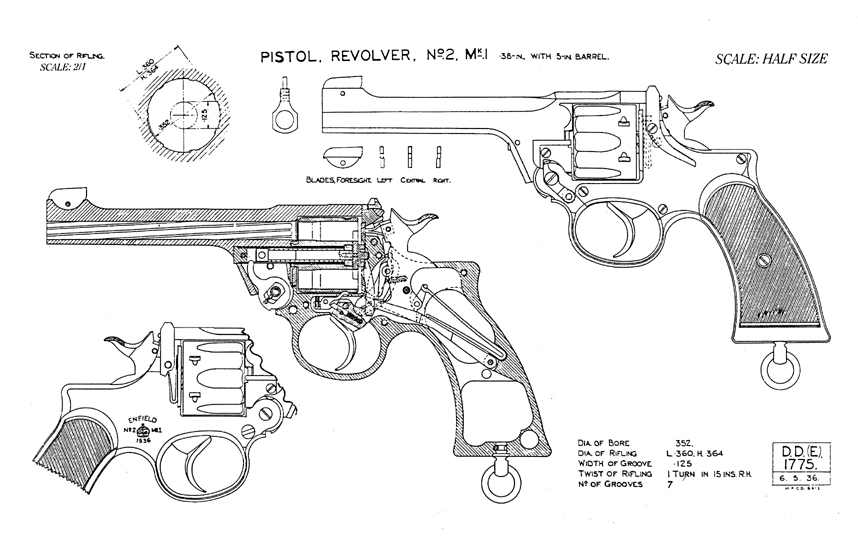

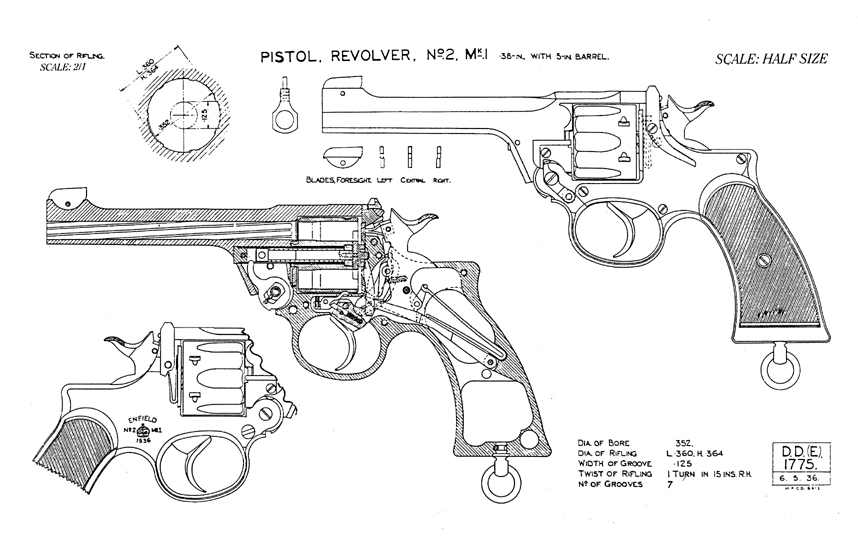

The Webley No. 2 Mark I revolver uses a rebound lever. Some of the older British Enfield and Webley revolvers did not. I'm not sufficiently conversant with the details of the older Enfields and Webleys to tell you which ones have a rebound lever and which ones don't. Here is a diagram of the later Webley revolver:

You can see the rebound lever here, and perhaps you can imagine how the notch in the rebound lever pushes at the base of the hammer and causes it to withdraw slightly, as the diagram shows. This kept the hammer back, so that its firing pin was not resting on the primer of a cartridge underneath it.

However, during World War 2, when these revolvers were much used by British and Empire forces, it was found that dropping them could still set off the cartridge underneath the hammer! The angle that the rebound lever and hammer meet, which allows the hammer to be pulled back, still allowed a sharp blow to force the hammer down, raising the rebound lever in the process. In other words, the rebound lever still did not make the double action revolver safe to carry with all chambers loaded.

Colt recognized this problem back at the turn of the century, and included a

HAMMER BLOCK in the 1905 "Police Positive" model.

Soon the hammer block was included in all three sizes of Colt double action revolvers.

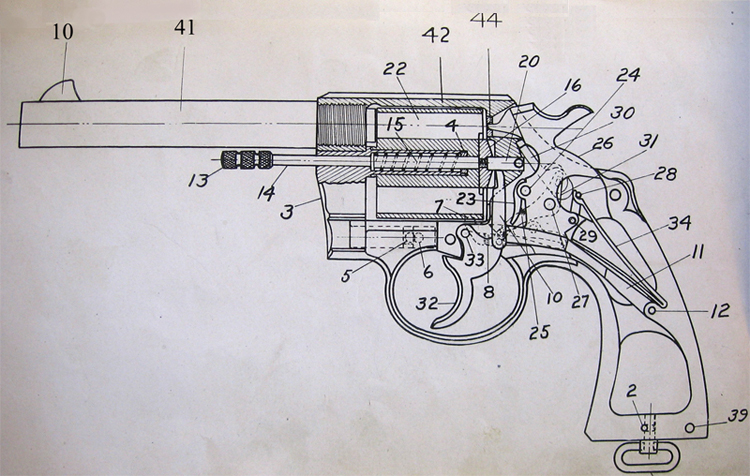

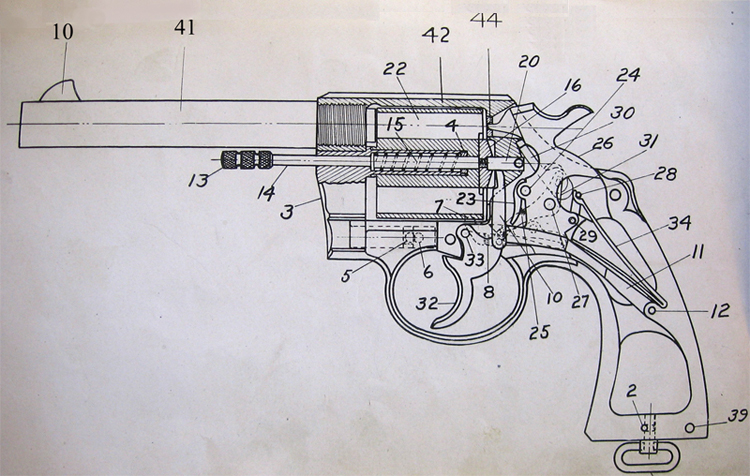

You can see the part as a little square that is between the hammer and the frame, near the point where the frame is cut away for the side plate. The following diagram shows the hammer block as part # 30:

This little piece of steel doesn't look very large, but there is no way the hammer can compress or break it.

Here, you see a Colt double action disassembled. part #7 pivots on a screw attached to the frame. The lower slot in part #7 rides on a pin in the trigger. The upper slot meshes with the hammer block, which is part #5

When the trigger is pulled back, it pushes the lower end of part #7 up, which pulls the hammer block down. This allows the hammer to fall all the way down so the firing pin can strike the primer of a cartridge. If you are carrying the gun with the hammer in the normal position, the hammer will be withdrawn slightly, but the hammer block will be up, preventing the hammer and firing pin from getting any closer to a live cartridge in the cylinder. Thus, it is impossible for the gun to discharge when it is dropped or struck on the hammer, even when all chambers in the cylinder are loaded. The hammer itself will break first.

Smith & Wesson uses a similar kind of hammer block, but their lockwork mechanisms are different. But, they offer safety like a Colt. I cannot say for sure that the hammer block is totally positive like a Colt -- I need to study it a little more. But if the S&W is working properly, it is safe.

Ruger revolvers, both single and double action, do not use a hammer block. They use a

TRANSFER BAR.

Here, you see a Ruger hammer, trigger, and attached transfer bar. (This is from a single action revolver, but the double action parts work exactly the same way.)

Note that, first, the transfer bar goes up with the trigger is pulled, and down when the trigger is released. This is the opposite of the way a hammer block works.

Secondly, note that the hammer does not have a firing pin attached. That part floats in the frame of the gun. Instead, you see that the nose of the hammer has two "steps." The top step is thick enough that it will strike the frame of the gun before the second step can hit the firing pin and fire a cartridge. But, when the trigger is pulled, the transfer bar comes between the hammer and the firing pin, and the second step push the transfer bar against the firing pin, firing the cartridge.

Note here, the transfer bar is raised by pulling the trigger, and the second step will strike it when the hammer falls.

Again, the trigger has to be pulled for the gun to fire.

The transfer bar system is simpler, however some folks have complained that the trigger doesn't have as good of a "feel" as hammer block lockwork. For most of us, however, we won't know the difference.

What does this mean?

The IOF Revolver is patterned after the Webley revolver. However, I understand that, at some point, IOF modified the lockwork to simplify it. I have read that the modified lockwork resembles a Smith & Wesson, but I have never seen a disassembled IOF. The parts diagrams that I have seen are not complete and I'm unable to assess the mechanism. Therefore, I can't give any opinion about how it works or how safe it is to carry when all the chambers of the cylinder are loaded.

I note that the IOF has a manual safety. To me, this is an admission that the lockwork is not safe to carry with a cartridge loaded under the hammer. Furthermore, if the safety does not positively lock the hammer from falling, it is a cheap fraud and a waste of time.

Owners of any firearm, including the IOF revolver, ought, in my opinion, to be familiar enough with the mechanism to know for sure whether it is safe to carry or not, in whatever mode it is carried. The original poster to this thread did not do that and nearly caused a catastrophic accident because of this. This should be a warning to all who use any kind of gun. As my Mother taught me, a word to the wise is sufficient.